Travelling in Myanmar under the Military Dictatorship

In 2003, I spent a month travelling in Myanmar (Burma) during an era when the military junta ruled the country, killed those protesting its rule and held Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest. After a brief period of partial democracy starting in 2016, the February 2021 coup has reinstalled these triple pillars of political reality from late 20th and early 21st-century Myanmar. This article is a snapshot of life in the country during that 2003 visit, and life as it may be again in 2021 with the junta having reasserted its power.

At the turn of the century, Myanmar received fewer than two hundred thousand foreign visitors a year, compared with ten million for neighbouring Thailand. This relative lack of tourists wasn’t because of a shortage of attractions — on the contrary, Myanmar contains some of the most impressive historic sites in Southeast Asia.

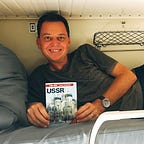

The country is known as the Golden Land, a description bestowed on it fifteen centuries ago by the Mon people who settled there. At Inwa, an ancient city in the north of the country, I found the July 1977 first edition of the once-banned Travellers’ Guide to Myanmar, which introduced the country this way:

The amazing temples, the Buddhist monks in their saffron robes, the most hospitable people in the world together with its beaches, magnificent lakes with their leg rowers, ice-capped mountains, silvery waterfalls, enchanting caves, alluring wide beaches, riverine beauty spots and thousands of pagodas mirroring the different epochs in history, art and culture have made her earn the name ‘The Pearl of the East’.

Despite this impressive pedigree, travellers have stayed away from Myanmar because of the isolation policy of the military junta that brutally ruled the country for half a century from 1962 and is now in charge once again after a five-year respite.

John Pilger, an award-winning journalist and filmmaker known for his investigative reporting in Southeast Asia, described the junta in the 1990s (then known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council) as even more oppressive than the infamous Khmer Rouge regime in 1970s Cambodia:

What sets SLORC-run Myanmar apart is slave labour and massive displacement of whole sections of the population. No [other] modern state, whatever its totalitarian stripe, has turned itself into a vast slave labour camp in order to ‘develop’. Certainly, Pol Pot tried it as a means of control, but none matches the SLORC in paving its way to ‘the market’ with such brutal audacity.

In the past, the junta made travelling in Myanmar extremely difficult for foreigners. Many places had been off-limits to tourists for decades — some still were in 2003 — and until the 1990s, the government only granted seven-day, non-extendable visas to foreign visitors.

While in the country, I met a Canadian woman who first went to Myanmar in 1980 and detailed her experience travelling there at the time.

‘Everything was very controlled back then,’ she said. ‘We had to stay in government-run hotels and use government transport. The whole country was very closed: no Coca-Cola, no imports, no foreign investment.

‘But the people were so friendly. They still are, but back then they weren’t accustomed to seeing tourists. They would invite you to their house, or pay your way, even when they didn’t have any money.’

These insights encapsulate Myanmar both then and — heartbreakingly — again now: a beautiful country full of delightful people who are at the mercy of a repressive government.

It was after dark by the time I arrived in Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city and the country’s capital at the time. Taking a taxi from the airport to the city centre, I caught a glimpse of Yangon’s most famous Buddhist temple and the most important religious structure in Myanmar, the Shwedagon Paya. Upon seeing the ninety-eight-metre-high gold stupa rising into the night sky, it hit me for the first time that I had arrived in the Golden Land.

As my introduction to Myanmar, Yangon was charming in a dilapidated way. It had a population of four or five million people — no one was quite sure exactly how many — but the chaos and traffic that cities like Jakarta and Bangkok seemed to thrive on was absent. The run-down buildings and old colonial structures from the British era had a certain appeal to them, and brilliant golden stupas abounded.

But it was the street life in Yangon that I most enjoyed watching. Main roads turned into produce markets and, sometimes, makeshift badminton courts. Restaurant stalls were on every corner, and people lined the streets from dawn until after dark, selling every item imaginable from microphones and calculators to hair bands and books.

The whole city was a grand bazaar. One traveller I met estimated that street sales drove eighty per cent of Yangon’s economy, and that wouldn’t have been much of an exaggeration.

On the streets, almost all local men walked around wearing a longyi, a type of sarong. An article I read in a weekly English-language newspaper, The Myanmar Times, explained that this was not customary in other countries:

Outside of Myanmar, most men wear pants. They sport slacks, trousers, jeans or shorts — anything with two distinct openings for the legs. In modern western society, it is considered inappropriate for a man to wear a skirt. For Myanmar men, longyis are not vehicles through which to make political or fashion statements. They are not expressing their über-comfort with their gender identity; rather, wearing skirts is part of their culture.

The continuation of endearing local traditions as a result of Myanmar’s isolation was a delight to the traveller. But separation from the rest of the world had been disastrous in other ways, sending Myanmar spiralling backwards in an age when many Southeast Asian countries had flourished.

This backwardness was evident immediately upon arrival. On the streets of Yangon, women set up stalls with typewriters and served as on-the-spot secretaries because ordinary Burmese people were unlikely to own a typewriter, let alone a computer.

Many people didn’t even have fixed-line telephones in 2003 — and I saw only one mobile phone in the month that I spent in the country — so entrepreneurs set up desk phones on street corners and charged for calls.

As for the Internet, that was barely even a dream in Myanmar in 2003. The junta had set itself up as the only Internet Service Provider in the country but had banned the web itself. Instead, it charged high rates in U.S. dollars for businesses just to be able to send and receive emails, which the government could then screen.

In order to contact my family at Christmas, I went into Myanmar’s equivalent of an Internet café — a grocery store with a computer — and paid what amounted to half a day’s salary for rolling low-cost cigarettes at a Burmese cheroot factory to send one message home.

In 2003, the junta published a daily English-language newspaper called The New Light of Myanmar, a propaganda tool for the government. Its main stories were little more than itineraries for top junta officials, and the pages were filled with slogans such as: Emergence of the state constitution is the duty of all citizens of Myanmar.

Each edition of the paper carried a table titled ‘People’s Desire’, which also appeared on red and white billboards in Burmese and English all over the country. The ‘People’s Desire’, according to the junta, was to:

- Oppose those relying on external elements, acting as stooges, holding negative views

- Oppose those trying to jeopardise stability of the State and progress of the nation

- Oppose foreign nations interfering in internal affairs of the State

- Crush all internal and external destructive elements as the common enemy

The main ‘internal destructive element’ was pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi, winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize and daughter of Myanmar’s independence hero General Aung Sun.

I saw an equestrian statue of the general in Bago, a small town eighty kilometres northeast of Yangon. My trishaw driver and guide cycled past the statue and said Aung San was still the most loved of all Burmese leaders.

‘His daughter is Suu Kyi. She won the Nobel Peace Prize. You know her?’

‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘Where is she now?’

‘In the jungle.’

‘Is she being held? Detained?’

‘Yes.’

Then he looked around nervously to see if anyone was within earshot, lowered his voice and said, ‘I am afraid to talk about this.’

Suu Kyi was under house arrest then, and now she is being detained once more. In between, when Myanmar transitioned to partial democracy in 2016, she became the country’s prime minister until being deposed in the February 1 coup.

‘Suu Kyi tries to get democracy in our country,’ a Burmese man told me in 2003. ‘But the government is very bad for her. She doesn’t do anything bad.’

He was taking a risk by even telling me this.

‘If we talk about the politics in the city, it is very dangerous for us,’ he said. ‘Just the talking. If we do talk about the politics, maybe we are dead.’

But no one else was around then and he talked openly about his hatred for the regime. I asked the odd question, but mainly just listened in silence as he detailed the government’s opium and heroin trafficking — something I had also read about elsewhere — and the people’s disdain for the junta, even within the ranks of the government and the military.

‘Are you hearing about ‘88?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘There was an uprising.’

Student-led and brutally supressed, it was Myanmar’s equivalent of the Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing the following year. Thirty-three years later, the situation is repeating itself following the February coup, in both the protests themselves and the junta’s murderous response.

‘Many students died,’ my new friend said of the 1988 uprising. ‘They killed them with a fire pipe, and if people were still alive, they killed them with guns.’

He spoke of chilling, horrific crimes, including students being beheaded and impaled.

‘They cut the head, and then they put the head on a stick — very bad,’ he said, recalling footage he had seen.

‘We have the movie, they made a video. We look at this. The problem was in ’88 and I watched this movie in ’92 or ’93. Some people, they killed with a knife. They cut the body and they threw it in the river. I have never in my life before seen anything like this.’

Many of the protestors who weren’t violently killed died anyway, he said.

‘The government, they put nearly one hundred people in one car. The car is very small. You know the pick-ups?’

I nodded, as pick-up trucks were a common form of transport in Myanmar. They are designed to carry perhaps twelve people, though it wasn’t unusual to see twenty or more Burmese piled in one. But one hundred?

‘Sometimes they put more than one hundred,’ he continued. ‘Almost everyone is dead because they don’t have the oxygen.’

One Sunday afternoon in Myanmar’s second-largest city, Mandalay, I headed to Mandalay Hill for a view over the city and was met at the bottom by a friendly Burmese man who taught English to university students.

‘I come here when I have spare time to polish my English,’ he said, and I walked up the hill with him.

‘Are you interested in Myanmar?’ the teacher asked me.

‘Of course.’

‘The people are very nice but the government controls everything with weapons,’ he said. ‘We don’t have weapons — only catapults!’ He fired an imaginary slingshot and laughed, but at the same time, he was being deadly serious.

It took about half an hour to get to the top of the hill, from where there were views of trees and stupas as far as the eye could see.

The teacher pointed to the northeast, and said that his home town, Mogok, was in that direction. ‘It is famous for rubies and jade, but it is a no-go for foreigners,’ he said.

‘Why can’t foreigners go there?’

‘The government wants to control the buying and selling. Our government is very greedy. It’s the same with teak.’ He pointed at the stacks of logs in the distance as he said this. ‘If I deal in teak I will be arrested and punished.’

As I walked around the viewing platform at the top of the hill, monks and other locals began approaching me, wanting to practice their English. I looked around, and noticed that each of the several other foreigners on the hill was surrounded by a handful of Burmese.

I had never seen anything quite like it before or since: there were dozens of them — monks, novices, teenage boys and girls, university students — latching onto tourists and striking up friendly conversations.

Some were shy and hesitant, but others were fearless. They wanted to know anything and everything about me, and all sorts of bizarre questions ensued: ‘Do you want to become Buddhist? Are there hurricanes in your country? Is Myanmar better than Thailand? Can you tell me what some of the famous sights are in Australia?’

The monks, in particular, relished the opportunity to use English to learn what life was like outside their closed and impoverished country. Later, I learned that in years past, the junta had imposed a ban on learning English for that very reason.

I told the English teacher of my amazement that so many Burmese people had walked to the top of Mandalay Hill — a sweaty, barefoot climb in tropical heat up hundreds of steps — just to speak English with tourists.

‘In downtown,’ he said, ‘we are not allowed to talk to foreigners unless we have a tour guide licence. If we are seen talking to foreigners and we can’t produce a tour guide licence, we could be arrested.

‘The police are here too sometimes,’ he continued. ‘They come in plain clothes. So we have to be careful when we talk about politics.’

When no other Burmese were within earshot, he told me that he estimated eighty to ninety per cent of the people were against the government, and then he revealed his personal feelings in an extraordinary outburst.

‘I don’t want to live in this country anymore,’ he lamented. ‘We know nothing. We live in the dark. We watch TV and read newspapers but it’s just the government blowing their own trumpet — “Look, we did this, we built a bridge, we built a dam” — it’s not for the people.’

And he wasn’t exaggerating. Several weeks later, an edition of The New Light of Myanmar actually carried a full-page story, complete with pictures, hailing the construction of 165 bridges during the junta’s reign.

The teacher chose his final words carefully and delivered them slowly, heightening their impact. ‘They are spoiling our country … systematically,’ he said.

I thought of George Orwell, as I often did in Myanmar because I was reading his novel Burmese Days about the country’s colonial era, which the author lived through as an imperial policeman in the 1920s.

But this time I was reminded of another of Orwell’s books, which was set elsewhere but whose imagined future resembles the past — and, now, tragically, the present — for the people of Myanmar: Nineteen Eighty-Four.