Lockdown Before Coronavirus: A Week in China’s Xinjiang Province During a Uyghur Uprising

With many national governments taking measures to stop the spread of the coronavirus, hundreds of millions of people around the globe have been ordered to stay home. It’s the second time I have been forced inside, although the first — in China 11 years ago — was under vastly different circumstances.

From early 2008 until mid-2009, I spent half my time in China, working on projects for the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games and the Guangzhou 2010 Asian Games and travelling around the country as much as I could in between.

These travels resulted in some amazing experiences, such as visiting a stone village outside Beijing and meeting the subsequently-named ‘Stone Village Team’ — four wonderful Chinese people who I’m still friends with today — and seeing some of China’s incredible natural wonders including the colourful lakes at Jiuzhaigou in Sichuan and the amazing karst scenery at Zhangjiajie in Hunan. I also found myself experiencing a less rewarding part of travel in China when I was surrounded by a S.W.A.T. team and evicted from a prefecture in Gansu which foreigners were prohibited from visiting at the time because of sensitivity surrounding its Tibetan cultural influence.

With my Guangzhou work commitments finishing at the end of June 2009, my wife and I headed to China’s vast western-most province, Xinjiang, to begin an overland journey along the Silk Road through Central Asia. But the trip was thrown into chaos only a few days after it began when an uprising of the Uyghur ethnic group against the Chinese government threatened to completely derail our plans.

What followed was an extremely tense week underscored by hotel lockdowns, communication shutdowns, cancellations, demands for non-existing permits, misinformation and propaganda.

This is how I experienced it, one day at a time.

Monday — “Hey look, there are two army tanks over there…”

We awoke in Turpan after an enjoyable couple of days’ sightseeing and took an early bus to Urumqi, arriving in the provincial capital at about 11:45am official (Beijing) time, or about 9:45am unofficial local time. This government directive for the entire country to conform to Beijing time is a feature of travelling in Xinjiang and can often cause confusion, but on this day it was the least of our problems.

Getting from the bus station to the train station for the 12:57pm train to Kashgar was harder than it should have been — several empty taxis waved us off to our bemusement and in the end we took a three-wheeler. On the way to the train station we saw two military tanks blocking a street, which I noted with interest but not comprehension.

I didn’t imagine that by far the worst violence in the history of the Uyghur-Chinese struggle for control of Xinjiang was taking place in the city right then and there.

The train left without incident and we still had no idea what had taken place. At 4:30pm I received a text message from a Chinese friend, who knew we were in Xinjiang, alerting me to 140 deaths in Urumqi (a total later increased to 156). I told her we were safe, but things could easily have been different. Our original plan had been to stay in Urumqi the previous night before taking the train to Kashgar, but because I was asked by my employer at the last minute to fly to Beijing and back the previous Friday to retrieve expense money from a bank account there, we lost a day of sightseeing and adjusted our itinerary accordingly.

On the train, some of the morning’s curiosities now began to make sense, but without knowing any real details, we were glad to be heading to Kashgar, still in Xinjiang but 1200km from Urumqi and on the doorstep of Central Asia. With our Kyrgyzstan visas in hand, we had planned to leave China the following Monday.

Tuesday — “Why are all the streets blocked off?”

We arrived in Kashgar at about noon the next day and, at first, everything seemed normal. We took a bus from the train station into the city centre and began walking towards an old city hostel that we had earmarked as our base for exploring Kashgar.

But soon it became apparent that significant security measures were in place in the old city of Kashgar, as all the shops were shuttered, some streets were blocked off and we saw a large police presence, including a military truck.

We decided to change plans and find a hotel in the new city while we figured out what was happening — not as easy then, given the available technology, as it would be today. At this point, texting internationally hadn’t been blocked yet, and I found out from my brother that in addition to the Urumqi protests, a non-violent protest of about 200 people had also taken place in Kashgar the previous day. We found a hotel, were lucky to get some supplies from the one store in the area that was open, and bunkered down for the rest of the day, eating two-minute noodles in our hotel room for lunch and dinner.

That afternoon, all domestic and international texting was blocked. The internet was also blocked by the time we checked into the hotel and would remain so for the rest of our time in China.

We did manage to see a Chinese TV news report on the Urumqi protests — though it depicted only Han Chinese as the wounded. Of course, we assumed that some or most of the deaths were a result of military firing on protesters, but being completely cut off from any information other than that produced by state media, we really had no idea what had happened in Urumqi.

A few days later, we were told by a foreigner who was still in Urumqi on Tuesday night that there were more clashes and deaths — unreported by Chinese media — and that she was forced to stay in her hotel room all afternoon and night. She said she saw all the shops close in an instant and Uyghurs preparing to defend themselves with poles and sticks.

Wednesday — “We cannot take foreigners…”

Leaving Xinjiang entirely seemed like the most sensible thing to do at this point, but our options for getting out of Kashgar were limited. All international routes out of western China went to countries for which we needed a visa in advance (and none of these could be obtained in Kashgar), and the only visa we already had — for Kyrgyzstan — wasn’t valid until the following Monday. Almost all domestic overland routes out of Kashgar went via Urumqi except those through Tibet and Qinghai (all or parts of which were closed to foreigners not on a tour). Flights only went to Urumqi and Islamabad. Besides, with no internet and no travel agencies open, we couldn’t even buy a plane ticket without going to the airport. It began to dawn on us that we were stuck in southern Xinjiang for the next five days.

With that in mind, the plan we settled on was to take the daily morning bus south towards the mountains, and lay low at a lake for a few days while the situation in the cities settled down. But at the bus station we were told that there wouldn’t be a bus for three days, and a sign scribbled in English said foreigners needed a permit to visit the lake, the first we had heard of that.

The lake was ruled out, then, and everything else was too; it seemed as though no buses or trains were leaving Kashgar at all. We saw Chinese people with train tickets to Urumqi trying to get them switched to bus tickets, but apparently without success, so it seemed as though Chinese and foreigners alike were stuck in Kashgar.

With no other choice, we headed back to the hotel we had just checked out of only to have the reception staff refuse to let us check us back in, giving us the 1980s-era “foreigners need to stay in a four-star hotel” spiel and saying that they didn’t have a permit to register us. When we reminded them that they had let us stay the night before, they said a new staff member had not understood the rules and had made a mistake. But since multiple people had been involved in checking us in, that was implausible. Instead, it seemed that China was going into permit roadblock mode.

Eventually we found a four-star hotel with rooms for about €30, bought some more supplies and bunkered down for the second straight day. Shops were still closed all day, and from our hotel window we saw five military convoys consisting of between seven and 10 trucks each pass by; the tension in the city was palpable.

With no other entertainment available, we turned on the television in our hotel room and almost immediately saw a propaganda advertisement that we had never seen before. It depicted China uniting in the face of adversity such as during earthquake relief in Sichuan the previous year, celebrating itself and its achievements including the Olympic Games and the Great Wall, and showing cultural images from minorities country-wide — though the Uyghurs of Xinjiang were noticeably absent from the montage. It was probably the most blatant piece of propaganda I had ever seen, including when I was in Burma under the military junta and in Cuba under Fidel Castro.

Later, we were told that two Uyghurs were shot by the military that day in front of the Id-Kah Mosque in the old city of Kashgar, and between eight and 20 more were arrested.

Thursday — “The Uyghurs will keep fighting!”

The Uyghur side of the story, as told to us by a local, went like this: about two weeks earlier, 62 Uyghurs from a village near Kashgar who were working in a toy factory in Guangdong province in eastern China were thrown from their fourth-floor dormitory and killed. The incident apparently occurred because a Han Chinese who had previously held one of the jobs wanted it back, and stirred up resentment towards the Uyghurs. The government only admitted to two deaths, and brought two bodies back to Xinjiang for burial. But they did not tell the parents of the deceased, and after burying the bodies — contained within plastic bags to hide the mutilation, we were told — the Chinese police guarded the tombs around the clock to prevent the villagers from digging them up and accessing the bodies.

On Monday, as a way to mourn those dead, Uyghurs in Urumqi gathered together peacefully for several hours. Chinese police tried to break it up, but the Uyghurs maintained that it was a mourning ritual and not a protest. Then, some younger Uyghurs turned it into a protest against Chinese rule, and that’s when all hell broke loose. Uyghurs and Chinese then began clashing in deadly fashion. And it apparently hadn’t ended there: we were told by another Uyghur that a passenger bus travelling that day from Kashgar to Korla, carrying mostly Uyghurs, was torched by Han Chinese civilians.

Despite the ongoing animosity, we finally ventured into Kashgar’s old city, encouraged by hotel staff telling us that everything was “normal” after two days of virtual lockdown. And if normal meant dozens of marching soldiers, a huge military blockade around the Id-Kah Mosque and an atmosphere that must have rivalled Cold War era Berlin, then normal it was.

Heightened security aside, the old city was a hub of Muslim activity: fruit, meat and bread sellers sold their produce on the narrow streets to veiled women while donkey carts passed by. It was for this kind of cultural experience that we had come to Xinjiang in the first place.

Friday — “You don’t have a permit.”

Needing to escape Kashgar for our own sanity as much as security, and with the public transport situation still uncertain, we hired a car and driver to take us south to Lake Karakul on a familiar road — the Karakoram Highway, which rises to the Khunjerab Pass at 4800 metres above sea level, crosses into Pakistan and then winds down through the mountains all the way to Islamabad. It was a fabulous trip, past Silk Road ruins, the glacier at Oytag, and barren, deep-red mountains to the gorgeous lake, ringed by 7000-metre snow-capped peaks. On this day, it was virtually deserted and was easily one of the most beautiful places we had seen in China and the single biggest highlight of Xinjiang.

But even here, four hours drive south of Kashgar, which was itself virtually the end of China, the security crackdown continued. In the afternoon, Uyghur and Kyrgyz men who inhabit the village on the lakeshore were prohibited from attending Friday prayers at the local mosque by Chinese police, as though 200 villagers in the middle of nowhere attending a religious service could actually threaten the might of China.

Then, at 1am Beijing time (11pm local time), Chinese police tried to evict us from the Kyrgyz yurt we were staying in while we slept and move us to a Chinese-run yurt. The concrete Kyrgyz yurts were built by the Chinese so the Kyrgyz herders could house tourists (for which the government, naturally, extracts taxes), so the whole operation was completely legal, but all of a sudden the police pulled out their trump card and said the herders didn’t have the right permits. Of course, they couldn’t actually obtain the permits, which served purely to allow the authorities to retain veto control over everything.

In the end, our guide resisted and we didn’t have to move yurts — and in fact slept through the whole thing — but two other foreigners in a nearby yurt were forced out in the middle of the night. What China hoped to gain by preventing Kyrgyz — not Uyghur — herders from making €4 per person per day for full room and board was beyond my comprehension.

Saturday — “Stay inside your hotel.”

Returning to Kashgar, we passed by a couple of temporary military checkpoints and were told by soldiers there not to leave our hotel once we got back into the city. They also said that Lake Karakul would be closed for the next three days, so we were extremely fortunate to have gone when we did.

Once we arrived in Kashgar, everything seemed open again, but the Han Chinese manager of our new lodging — an old city hostel — said things were too quiet and that he expected something to erupt within three or four days. Internet, text messaging and international calling were still blocked, and the military presence in the old city remained enormous, even larger than earlier in the week.

Sunday — “There will be police there…”

The biggest attraction in all of Xinjiang — the famed Kashgar Sunday market, which we had wanted to visit for at least five years and for which all our planning was done to accommodate — was, of course, cancelled. Given that Chinese police had blocked 200 villagers from going to a rural mosque two days earlier, it was obvious that 100,000 Uyghurs would not be permitted to descend on their weekly market in the province’s second-biggest city. Despite this, we were still told that the market would be open, so we went to one of the two sites only to find that 95 per cent of stalls were closed and hundreds of soldiers were stationed nearby. There, we met travellers who had just come from the livestock market, where they saw a few sheep and nothing else — it was almost completely deserted.

This was a great disappointment, but at least we didn’t have the experience of a couple of other travellers we met, who had driven for hours to begin their overnight camel trek in the desert only to be turned back once they got there by Chinese authorities “for your safety”. So from an empty desert, they were returned with a police escort to a hostel in Kashgar 400 metres from the Id-Kah Mosque, where there had reportedly been a shooting four days earlier and where hundreds of Chinese soldiers were stationed around the clock, pointing their guns at us as we walked past.

Monday — “Can we really leave?”

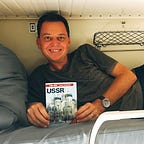

With our Kyrgyzstan visas now valid, we could finally leave China for the relative safety of the former Soviet Union — if all went well.

The weekly bus from Kashgar to Osh was an hour late in departing but I was so ecstatic that it wasn’t cancelled that the delay did nothing to dampen my spirits. Foreigners taking buses from Kashgar to Urumqi in recent days had reported at least 20 temporary military checkpoints along the way, so we expected more of the same heading to the Irkeshtam Pass. But in fact there weren’t any, and when I surveyed the rest of the bus it made some sort of sense; it was extremely difficult for Uyghurs to obtain passports, so there were none on this bus — only Uzbeks, Pakistanis, Kyrgyz and five Westerners.

The bus took about six hours to reach the border, and all the while I feared that we could still be turned back at the last moment, as had happened to the desert travellers — but we weren’t. I somehow escaped the bag search at the border, where the Chinese guard went through the photos on my wife’s camera and ripped the map page out of someone else’s guidebook because it didn’t depict Taiwan as part of China. The formalities on both sides were arduous and the whole process took about three hours, but eventually we made it through.

It was almost hard to believe, but the proof was right there in our passports: a Chinese exit stamp, signalling that a week of frustration, uncertainty and more than a little fear was finally over.