Four Objects, Four Stories: Dreaming about Travel in the Age of Coronavirus

With many of us in lockdown, flights largely suspended and future plans up in the air, where do we turn to satiate the travel bug?

Travelling in the age of coronavirus has been reduced to daydreaming, and as I look around my apartment in search of inspiration, my gaze falls on four objects and I’m reminded of the travel stories they tell.

These aren’t items I bought at souvenir shops, and in English I wouldn’t even describe them as souvenirs. But each one is actually a souvenir in the fullest sense of the French meaning of the word: a memory.

Myanmar, 2003 🇲🇲

I spent my first afternoon in Myanmar searching for a copy of Paul Theroux’s celebrated travel book The Great Railway Bazaar in the country’s then-capital, Yangon. Bagan Books reputedly had the most extensive collection of English books in Myanmar, but it turned out to be a disappointingly small one-room store with two bookshelves, a glass cabinet and virtually no chance of stocking the book I sought. Perusing titles like Betel Chewing Traditions in South-East Asia, I became resigned to travelling in Myanmar without the companionship of Theroux, who had visited the country 30 years earlier as part of his journey by train across Asia.

And then it suddenly appeared before my eyes and I couldn’t have conceived of a more wonderfully appropriate edition. Out of place and hidden between some black-covered volumes about the British colonial era was a weathered book wrapped in faded pink cardboard with an off-centred image photocopied onto the cover. It was barely legible, but I could just make out the title: The Great Railway Bazaar. The entire book was a photocopy of the 1976 third edition, complete with an attached green string bookmark.

I thought the author himself would have been proud to find it, and even for a small Burmese fortune of US$8, I was delighted with my purchase.

My prized book in hand, I travelled throughout Myanmar with my then-girlfriend (now wife) Wendy for several weeks and we eventually arrived in Pyin U Lwin, a colonial town more than a thousand metres above sea level. When Theroux visited, the town was still known by its British name, Maymyo. But then again, in 1973 Bagan was Pagan, Yangon was Rangoon and Burma was still the country’s official name. And that wasn’t all. On the photocopied map at the front of The Great Railway Bazaar, there were places like Ceylon, the USSR and North Vietnam. And cities, too: Peking, Saigon, Leningrad — how the world had changed.

Pyin U Lwin had changed as well. Theroux’s description made it sound like one of the loveliest places in Asia. Upon arrival at the train station in Maymyo, he was greeted by ‘about thirty stagecoaches — wooden carriages with faded paint and split shutters, and drivers in wide-brimmed hats and plastic capes flicking stiff whips at blinkered ponies’.

Thirty years later, motorbikes, trucks and jeeps were Pyin U Lwin’s main forms of transport. Much of the colonial architecture was gone, too, replaced by more modern buildings with satellite dishes on their roofs. The stagecoaches could still be seen around town, and were as picturesque as in Theroux’s description, but they seemed to exist more for nostalgia than for any practical purpose. They were rarely used and mostly sat idle on street corners.

In any case, I wasn’t there for the town itself. I had come to Pyin U Lwin for the same reason Theroux had: to take the train across the Gokteik Viaduct, a magnificent feat of early twentieth century railway engineering built by the Pennsylvania Steel Company in 1900 when Myanmar was a British colony.

It was cold and misty when we walked to the train station at 7:30am. Kumar, a local we had met the day before, said Pyin U Lwin was a British town with British weather, and he was right. On this morning, the entire town was rugged up in beanies, scarves and Russian fur hats — anything went. I saw one man with a Coca-Cola towel wrapped around him for warmth.

The train station wasn’t large, and it needn’t have been because only two trains passed through it each day. We bought ‘ordinary class’ tickets — itself an achievement, as foreigners were usually required to travel first class — to Naung-Peng, the station after the viaduct. The train, which had begun its journey from Mandalay at 4:45am, arrived at Pyin U Lwin station at 8:10am.

We hopped into one of the ordinary class carriages to find that the description was too kind: the carriage was filthy and filled with an awful stench that emanated from the lavatory, and the seats were like wooden park benches — only less comfortable. The carriage was packed with locals, but no one had suitcases. Instead, the luggage racks were filled with wicker baskets and rice sacks. More baskets were tied to the racks and more still, filled with fruit, blocked the aisle.

At one minute past nine, the 8:15 train to Lashio chugged out of Pyin U Lwin station. It was the first train I had taken in Myanmar, and it was remarkably similar to the bus: slow, bumpy and uncomfortable.

I decided it was the worst train I had ever caught, yet I was thrilled to be on it.

This was what travel was all about: riding on a train like this, huddled up and freezing but never once considering closing the wooden shutter despite the chilling wind. I looked out the window and saw sunflowers that didn’t belong in the morning fog and a Christian cemetery that did. I saw a man taking a bath by pouring buckets of water from the stream over himself and I shivered when I thought about how cold it must have been. In the rice fields, the women wore wonderfully quaint cone-shaped straw hats, even though the sun had yet to appear. They all looked up when the train passed; the railroad remained a novelty despite being more than a century old.

By 11:30am the mist was gone, the sun was out and I caught my first glimpse of the viaduct in the distance. It was as grand as I imagined but where I had pictured arches, there were a series of massive steel pylons instead.

The closer we got to the viaduct, the slower the train went. It snaked its way towards the enormous bridge, so that it was on our left side, then our right, then our left again. We finally reached the viaduct about half an hour after I had first sighted it, and slowed to a crawl as we started to cross it. I put my head out the window and saw that many others were doing the same. Far below us was the gorge; at the bottom was a pretty little stream with some small rapids. Rising from the stream on one side were luscious green trees, almost rainforest-like; on the other were dramatic cliffs, bearing down on the ravine. It was the most beautiful natural sight I saw in the four weeks we spent in Myanmar.

It took three or four minutes for the train to cross the viaduct, and soon after we had to go through two short tunnels cut into the rock. There were no lights in second class, and it would have been pitch black had a Burmese man not been lighting his cheroot just as we entered the first tunnel.

It was another half-an-hour to Naung-Peng, where we got off, bought a spicy noodle lunch from a vendor and waited for the return train, which was more than two hours late. There were no seats left in second class, and several passengers, assuming that we had bought the more expensive tickets, pointed us towards the first-class carriage. Since standing for three-and-a-half hours was the only other option, we took the hint and headed that way.

First class was hardly better than second. There were cushioned seats and a light for the tunnels, but that was about it. The carriage wasn’t much cleaner and it still smelled of excrement. There was a subtle difference in the passengers, though: several men wore pants instead of the more typical Burmese longyi, some smoked cigarettes and not the much cheaper cheroots, and they tipped the lute player more.

As we chugged away, I took one final look at the viaduct before settling into my seat for the return journey to Pyin U Lwin. When we finally arrived, it was almost dark and 13 stagecoaches were waiting to meet the train. It seemed some things hadn’t changed since Paul Theroux’s day, after all.

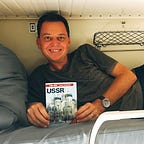

Kazakhstan, 2009 🇰🇿

Kazakhstan is the most accidental country I’ve ever visited. I didn’t intend to go there at all — much less bring back an object that I’ve held onto for more than a decade — but it became the only viable backup plan when we were travelling overland through China and Central Asia and Wendy couldn’t get a visa for Tajikistan.

We hastily put together an itinerary for Kazakhstan and travelled 3000km through semi-desert scrubland by train, a journey so off-the-beaten-path that one local woman told us we were the first foreign tourists she had ever seen. Even today, plugging the end points into Google Maps returns this result:

‘Sorry, we could not calculate transit directions from Almaty, Kazakhstan to Aktau, Kazakhstan.’

The main reason we journeyed across the length of Kazakhstan to begin with was to join Muslim pilgrims in their journey to the tomb of Beket-Ata, an 18th-century Islamic holy man, in the desert near Aktau. Thankfully, given the time and effort expended, it was quite extraordinary — not only the highlight of our three weeks in Kazakhstan, but one of the most spiritual experiences of my life.

At dawn opposite the bazaar in Zhanaozen, two hours from Aktau, a handful of jeeps and 4WD minibuses were waiting for pilgrims making the journey through the desert to Beket-Ata. We joined a local family of seven — four men and three women, including an old lady who had only one eye and could not walk without support — in a minibus, and by 8am we were on the road.

Leaving Zhanaozen, we passed hundreds of oil wells on the side of the highway — more than I had ever seen, even having lived in Qatar. Soon the sealed road ended and we drove through a desert that was more interesting than any we had seen in Kazakhstan. Here there were rock formations and plateaus in a mix of whites and pinks and everything in between, and none of the flat shrubbery that had completely dominated the landscape since Almaty.

Reaching our first stop at Shopan-Ata, we performed ablutions with the other pilgrims and were treated to the first of five meals that day — all provided free of charge. It was a surprisingly good spread of breads, meats, vegetables, fruits and sweets, and was much tastier and more varied than I had expected.

We walked through a nearby necropolis to an ‘underground mosque’, a surprisingly homely cave-like room with carpets covering the floors and a hole in the ceiling offering light. We sat with the pilgrims as they prayed and performed certain rituals which seemed to be derived from ancient regional beliefs rather than orthodox Islam, including whispering — praying? — to a tree branch in the middle of the room and then circling it three times.

To visit Shopan-Ata’s tomb in an adjacent room, I needed to cover my head. The mosque’s imam gave me a blue and white taqiyah (skullcap) for the purpose, and when I tried to return it later he wouldn’t let me and encouraged me to keep it, a touching gesture that I have never forgotten. It wasn’t that this taqiyah was particularly special — it was the kind of mass-produced skullcap with alternating blue stitchings of mosques and palm trees that is sold for a few dollars at shops throughout the Muslim world. But it was this generosity and willingness to include us, as clearly the only tourists there that day among over 100 pilgrims, in all activities — washing, eating, praying and sleeping — that made the whole journey so rewarding. As a mark of respect and appreciation for our hosts, I kept the skullcap on throughout the pilgrimage.

After leaving Shopan-Ata we continued for another two hours or so to Beket-Ata, where all the pilgrims would spend the night. We were befriended by a woman from Aktau named Baktagul who spoke English reasonably well and was staying indefinitely at Beket-Ata to pray for her son, whom she described as having a ‘psychological illness’ that could only be cured by spirits and not by a medical doctor. She told us stories about Beket-Ata — she said she knew enough to fill a book — and was delighted when we saw eight goats on our way to and from the tomb, as the holy man appears as a goat to pilgrims of good hearts, and as a snake to those with bad hearts.

The tomb of Beket-Ata was closed to all visitors, but the adjacent underground mosque was open, and we entered with Baktagul, her son, and another young man who the previous day had walked 16 hours through the desert from Shopan-Ata to Beket-Ata. Inside the cave, the imam sang an Arabic prayer in a beautiful, moving voice that I will not soon forget. It was incredibly surreal to hear this prayer inside an otherwise silent cave in the middle of the desert.

In the evening, all the pilgrims ate together and we slept on mattresses on the floor. At 3:30am we were woken for breakfast and by the time the sun rose we were back in Zhanaozen. Two hours later in Aktau, tired but content, I was overlooking the mythical-sounding Caspian Sea, awaiting a train to Uzbekistan and clutching my skullcap full of memories.

Ethiopia, 2011 🇪🇹

One of the joys of travel is discovering the unexpected — that delightful village you’d never heard of, that random encounter with a friendly local, that on-a-whim decision that turned out to be a masterstroke. Even in the age of bucket lists and pre-bookings, the experiences you end up enjoying the most while travelling often aren’t the ones you thought they would be before you set out.

Case in point: Ethiopia.

As perhaps the most distinct country in Africa, Ethiopia was somewhere I had wanted to visit for years and when I finally made it there, its major attractions didn’t disappoint. I marvelled at the incredible rock-cut churches of Lalibela, giddily explored the out-of-Africa castles in the Tolkienesque-sounding town of Gonder and stared nostalgically at an ancient obelisk in Axum that had once stood in Rome when I lived there before it was repatriated.

For all of these extraordinary places, however, my lasting memory of Ethiopia is simply walking in the countryside — and everything that entailed.

Led by a local guide, a friendly and outgoing young woman named Brehan, Wendy and I set out on a three-day community tourism hiking trip in the Tigray region of northeastern Ethiopia. Tigray is a little-known but spectacular area where the landscape alternates between dramatic sun-baked cliffs and fields for growing tef, the grain used to make the ubiquitous Ethiopian bread injera that is eaten three times a day. Dotted with picturesque rural houses and historic churches that date as far back as the sixth century, Tigray was the perfect place to hike in the countryside — and if that had been our whole experience, without any other human interaction, it would have been a wonderful trip.

But this was community tourism, after all, and the visitors’ brief that we received before departing indicated that not only would we have a chance to meet local people, but that this cultural exchange would be just as fascinating — or even more so — for them as it would be for us:

‘The local people have been given some awareness training but please do understand that they do not see many farenjes (foreigners) and will be amazed by you, your behaviour and your general ways.’

The community tourism NGO had done an admirable job of educating the Tigray population about the occasional presence of tourists and of putting revenue back into the community. The villagers we met understood that our mere presence benefitted them financially and as a result they were genuinely friendly towards us and the whole trip was refreshingly free of requests for money or attempts to sell souvenirs — almost to a fault, as it turned out.

On our second night in Tigray, we were invited to a family baptism ceremony, which gave us an amazing window through which to view local life and customs. We ate tihlo, a northern Ethiopian specialty in which balls of flour are dipped into a spicy sauce and eaten communally, and drank homemade beer called t’ej. We had been drinking this regularly while in Tigray — as advertised pre-trip in the visitors’ brief, which read:

‘Alcohol is quite normal in rural Ethiopia and no one will be upset by your drinking. In fact you will probably be asked to share some local beer. However, do remember the sites are all close to cliffs and too much alcohol may not be a good idea.’

Although the home brew was too sour for my palate and usually had bits floating in it, it was a great way to connect with locals — away from cliff-tops, naturally. The villagers drank it regularly, even on Sunday mornings immediately after church, and always offered us some.

We may not have been enamoured with the beer, but it was made more tolerable at the baptism party by the rustic clay goblets we drank from. The goblets were wonderfully imperfect, as homemade as the brew and a brilliant encapsulation of life in Tigray. The bases were a bit wobbly, the rims were not quite circular, the colour wasn’t uniform and they were all slightly different sizes. But more than all the souvenirs in the tourist shops of Lalibela, they struck me as the perfect memento of our time in Ethiopia.

‘Do they make these cups to sell to tourists?’ I asked Brehan hopefully.

‘No, they just make them for themselves,’ she said, implying that the quality wasn’t good enough to be desirable for tourists.

But I loved them, and a few minutes later, I tried a different approach. ‘Will we pass a market tomorrow where I might be able to buy cups like these?’

‘No,’ she said, and after a few moments’ silence, sensing my disappointment, she asked, ‘Do you want me to ask them if they will sell some to you?’

This was apparently such a strange request that the family who owned the goblets had no idea how much to ask for them, and an animated discussion ensued. Finally, Brehan returned and said they would sell two goblets for about one euro each, which I happily paid to the locals’ bemusement.

The next day was our last in Tigray and it was with some sadness that we left its picturesque landscapes and warm-hearted people behind for the big smoke of Addis Ababa and, a few days later, home.

I brought the goblets with me and displayed them in our living room. Nearly a decade later, despite moving to a new country in the meantime, they’re still on display, and when we rent out our apartment while travelling, they’re one of the first things I lock up. When we return, I take them out again and I’m always happy to drink from them — as long as it’s not Ethiopian home brew.

Japan, 2019 🇯🇵

Discovering new cultures is one of the biggest rewards of travel, so when I’d heard people mention the culture shock they experienced when visiting Japan, I tended to brush it off as something that wouldn’t affect me. Since my ill-advised trip to Morocco 18 years earlier as a new traveller, culture shock wasn’t something I had really experienced; learning about and immersing myself in a new culture was why I went to these countries in the first place.

But then I went to Japan, and it all made sense — or, rather, almost nothing made sense, which was precisely the point.

The rules, the etiquette, the greetings and the toilets were all a mystery. What’s considered aesthetically pleasing? What’s frowned upon? What do you do in an onsen? All of it was so foreign to me even after a lifetime of travel.

Perhaps the biggest adjustment, minor as it may sound, was the constant removing of shoes. In Japan, you have to take your shoes off inside virtually everywhere — houses, hotels, some restaurants, temples, and even castles where you have to put your shoes in a plastic bag and carry them around with you until you reach the exit. In hotels, you typically have to remove your shoes at the entrance and put slippers on, but then there are different slippers for the bathroom, and if you’re staying in a tatami mat room as Wendy and I often did, you’re not allowed to wear slippers on the mat and need to remove them just a few moments after putting them on.

All of this is to say that the whole shoe removal system is very ingrained in the culture and is fascinating in its own way — but one that takes some time to get used to as an outsider.

Gotoku Tei restaurant in Nagano is down a set of stairs from street level and hard to find, but worth it for the delicious food, the friendly owner and, above all, the shoe storage — of all things. When we finally found the restaurant on a chilly November evening in the one-time winter Olympic host city, we had to remove our shoes upon entering, something I was now getting used to after several weeks in Japan. But instead of leaving our shoes on the floor or a shelf, we were two use one of the two fabulous, old-fashioned wooden shoe lockers, which were unlike anything else I saw in Japan.

The lockers were wonderful pieces of furniture by themselves, but the most endearing feature was the locking system: wooden planks with Hiragana and Kanji characters printed on them and different slits in each plank to make each one uniquely fit one metal lock. Diners take the plank-keys with them to their table, and at the end of the meal they use them to retrieve their shoes. The system was ingenious, traditional and practical all at the same time.

We went to the restaurant twice and chatted a bit with the owner, who had lived in the States years ago and spoke English at a high level. The second night, I made sure to bring my camera to photograph the shoe locker and as we were leaving, I started taking a few shots. The owner came by and we started talking about the locker and how much I liked it, while I continued to snap away from different angles, trying to get the right shot.

‘Wow, you really like it!’ he said, and to my complete surprise, he pulled out two spare plank-locks from a drawer and gave them to me as a gift. It was a wonderful gesture from a lovely person and I was very moved by it. We had been travelling in Russia and Asia for nearly five months and the only other keepsakes I had from the entire trip were a few Soviet pins, so I was delighted to receive the planks just to have something to take away from the journey.

But it was more than that, of course. Without the lockers, the planks were no longer functional, but their true value to me was measured not by their usefulness but by what they represented. And if Japan’s age-old practice of gift-giving could serve up fond memories on wooden planks just like that, then this was one aspect of Japanese culture I was glad to be shocked by.